2025. We had barely peeled off the price tag of a new year when news broke out that parts of Southern California had been overtaken by flames. TVs and phone screens glowed a horrific orange as back-to-back clips played the inferno burgeoning through idyllic landscapes, historical neighborhoods, and symbols touting an impenetrable modern world. At one point I even saw a McDonald’s engulfed in flames, another hasty screenshot used by evangelicals for their digital proselytizing of the end times. As the square miles of scorched earth continued to spread under the watch a seemingly incompetent mayoral office, people began to flock to social media in order to grapple with the unprecedented destruction.

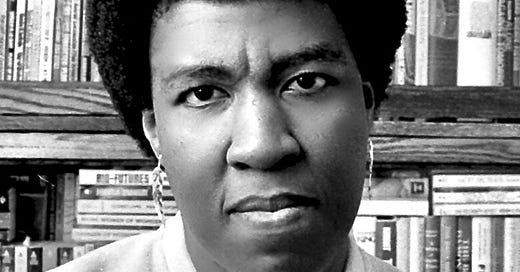

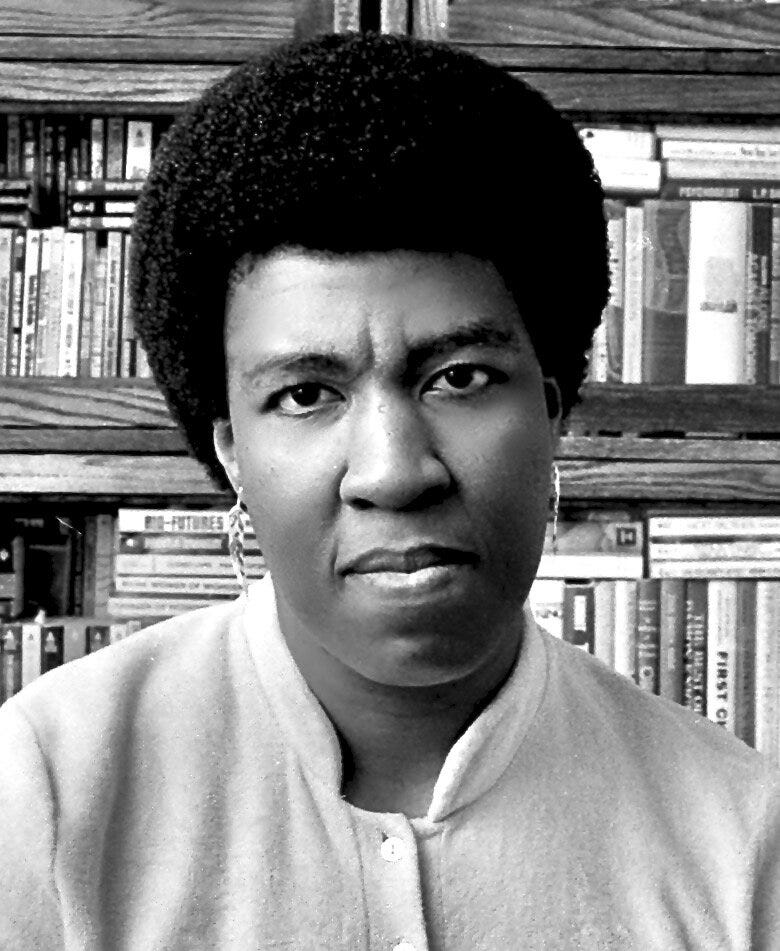

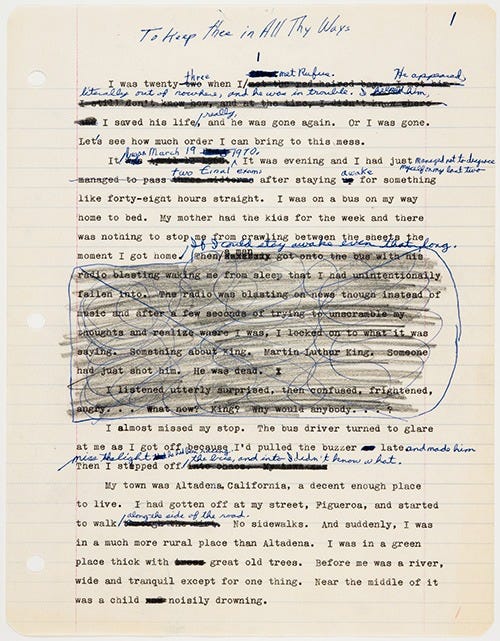

As a celebrated artificer of science fiction and social critique, author Octavia E. Butler and her quotes from her Parable series have gained a lot of traction lately. It starts with Parable of the Sower, which captures the years 2025 to 2027 and is told through the perspective of Lauren Olamina, a Black teenaged girl. Olamina has grown up in the outskirts of L.A., a frail version of its former self brought to its knees by incessant fires, climate change, political corruption, and greed. The first book follows the protagonist as her community experiences an even deeper decline. Since the fires began, I have also seen some push back over the parallels taken from the sobering tale penned by Butler, an Altadena native, as being as useful as a pail of water to douse out the flames. This argument has piqued my interest, as I had finished Parable of the Sower just a few months before.

For those who have yet to read it, it’s a visceral read. It’s full of rapings, beatings, murder, and poverty. There were moments where, after reading a troubling passage, I would promptly close my paperback and fold myself into the fetal position. Maybe what is most startling is that although Butler started the series in 1993, the world she imagined seems much closer to reality than we’re comfortable with. Yet, I can understand the frustration of quoting Butler when you’re the one sifting through wreckage and trying to exist amid the loss and uncertainty.

But how do you talk about fire? How do you talk about the man who laid just feet from where his house sat, clutching a water hose while the flames made a skeleton of his family home? We know that fire is inherently neutral. However, outside of the bounds of ritual and natural order, fire thrives as an agent of chaos, hungry and indifferent. And as a metaphor, it will simply turn its side to eat into the hard-fought paths to equity and visibility for marginalized groups, eat into the schools and hospitals and churches in search for immigrants, its belly rotund in greedy dismissal. How do talk about the fire that wants to consume us all?

Throughout the book, Olamina proves to be an excellent leader, rarely shirking from an opportunity to speak up and stir up the courage she and her peers need to keep going. When her community must come to terms with the likely death of a member gone missing, Olamina references Biblical passage Luke 18: 1-8 during an impromptu sermon to rally her neighbors:

‘We have God and we have each other. We have our island community, fragile, and yet a fortress. Sometimes it seems too small and too weak to survive. And like the widow in Christ’s parable, its enemies fear neither God nor man. But also like the widow, it persists. We persist. This is our place, no matter what.’

Whether in the physical or digital realm, wherever we are together is our place. How we speak to and about each other is as real and important as the walls that enclose us or the social platforms we run to to laugh and cry. Olamina’s exhortations play a crucial role in helping her loved ones—and herself—move forward. God knows the many times my peers have helped me do the same.

Octavia Butler passed away before she could complete her series (there was also Parable of the Talents, and then a third in the works). Although I believe that Butler is a relevant resource in today’s dialogue concerning national and international affairs, I don’t think Butler was a dealer in doom and gloom. Butler was a powerful, observant storyteller who captured the depth of how the choices we make ultimately affect the collective, as creators and destroyers of our world. Though Butler is not here to finish her story, we still can.

I am not sure if we will always have the language to speak to grief, to fill chasm of devastation natural or man-made. What I am confident of is the sacred strength found in community trust and care. The ways we come together to educate, edify, and share our resources. May our words be a comfort and critique of a dynamic world of our shaping. May our words empower us towards compassionate action for our neighbors. May our words be vessels joy and purposeful interrogation. May our words help us imagine and realize a habitable world for all and commit ourselves to each other even in ash and smolder.